It’s a twister!

by chuckofish

Yesterday was the anniversary of the February 10, 1959 “tornado outbreak” in St. Louis. I was not-quite three years old so I don’t remember it and luckily we lived in a part of town that was not hit. However, the F4 tornado did sweep through my current stomping grounds–Warson Woods, Rock Hill, Brentwood–on its way to the city.

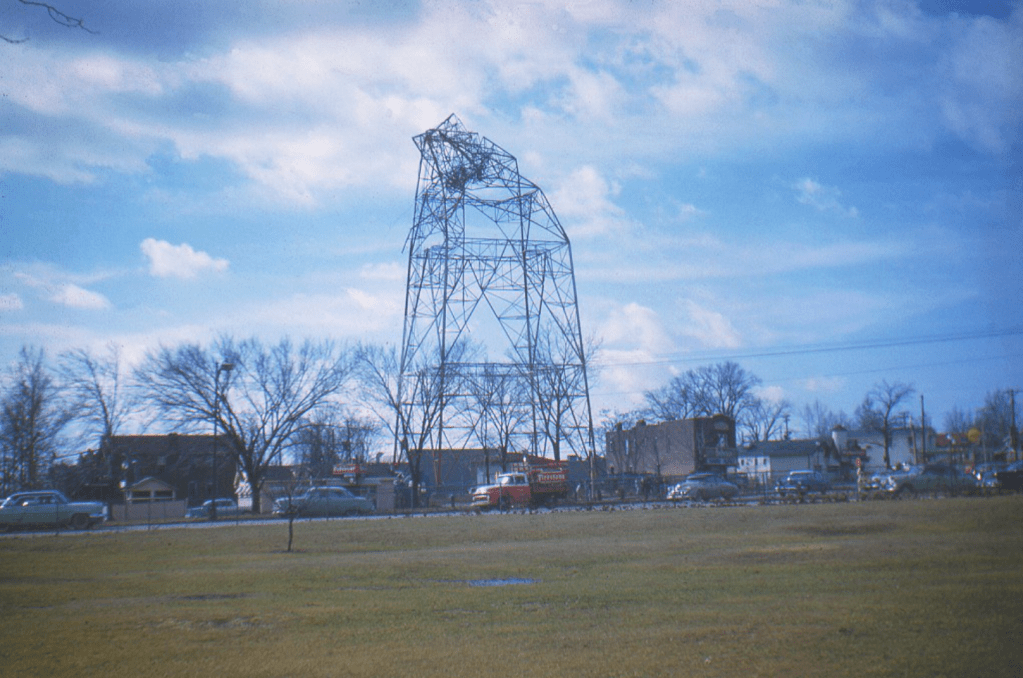

It toppled the Channel 2 television tower and one of the Arena’s two towers before moving on to devastate the area around Boyle and Olive Streets (Gaslight Square).

The tornado was on the ground for at least 35 minutes, traveled 23.9 miles (38.5 km), was 200 yards (180 m) wide, and caused $50.25 million is damage. 345 people were injured and 21 others were killed, making it the third deadliest tornado in the city’s history.

Interestingly, the heyday of Gaslight Square was actually kick-started in the aftermath of the city’s 1959 tornado outbreak, which caused severe property damage but also led to an influx of attention and insurance money. Business owners took advantage of this to revitalize the local economy. It became a very hip place to hang out–even my parents went there. Entertainers who performed in the clubs included: Miles Davis, Bob Dylan, Barbra Streisand, Judy Collins, the Smothers Brothers, Phyllis Diller, Woody Allen, and so on…

A 1962 episode of the TV show Route 66 titled “Hey Moth, Come Eat the Flame” was set and filmed inside The Darkside jazz club. How cool can you get?

Gaslight Square didn’t last long, however, and the Board of Alderman, who had officially renamed the district on 24 March 1961, retired the name in December of 1972. Easy come, easy go. C’est la vie.

P.S. I watched the Route 66 episode and besides the scenes in Gaslight Square there are scenes shot at the Chase Park Plaza on Kingshighway and the old Rock Hill quarry (which is mostly filled in now) and in some bowling alley I could not identify. It’s worth checking out for that!

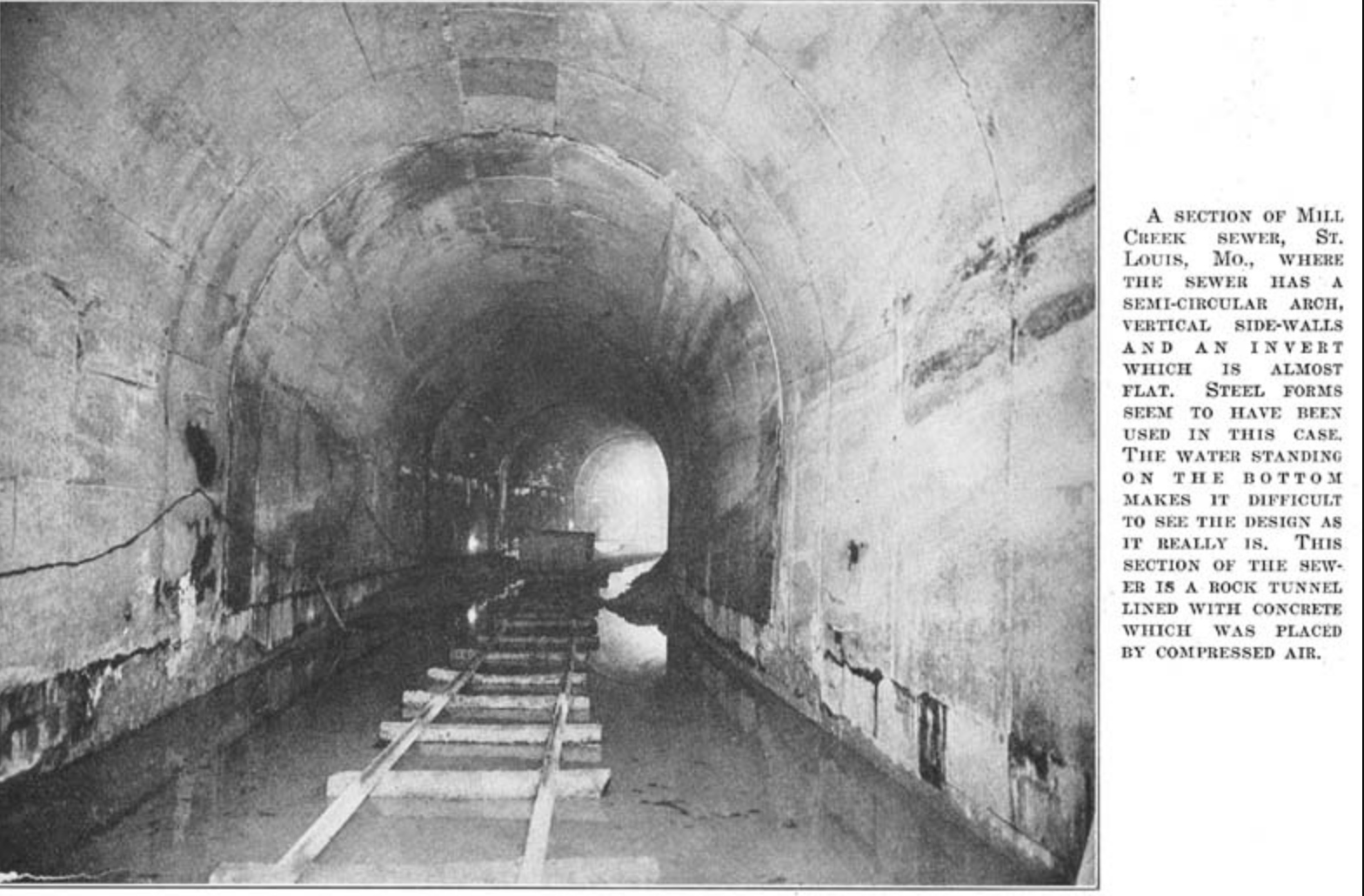

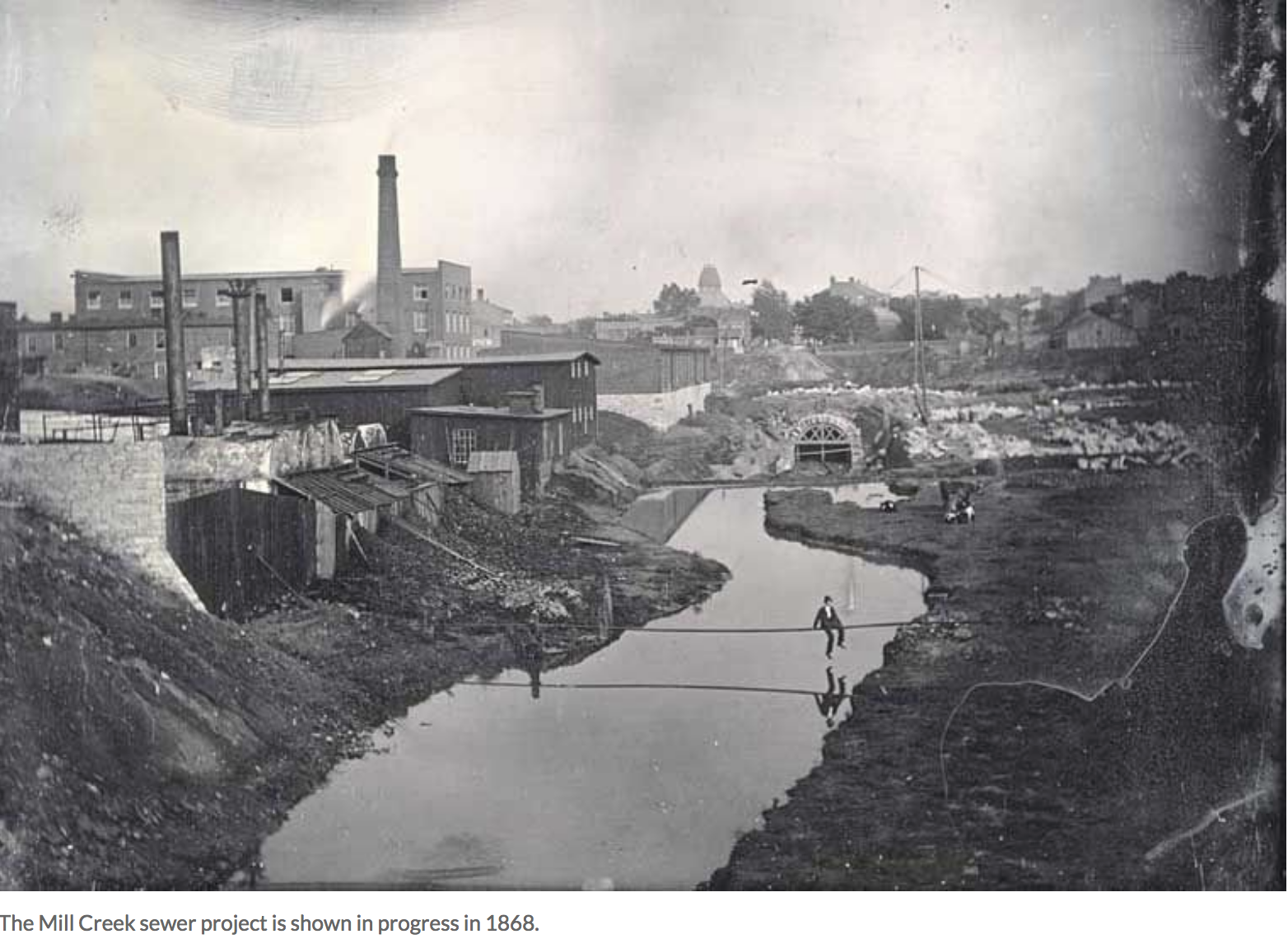

When the sewer was finally finished all the way to Vandeventer Avenue in 1890, it was considered the marvel of its time. It measured twenty feet wide, fifteen feet high, and more than three miles long. Wider than a single railroad track tunnel, the sewer pipe was described as large enough “to allow the passage of a train of cars or a four-horse omnibus.”

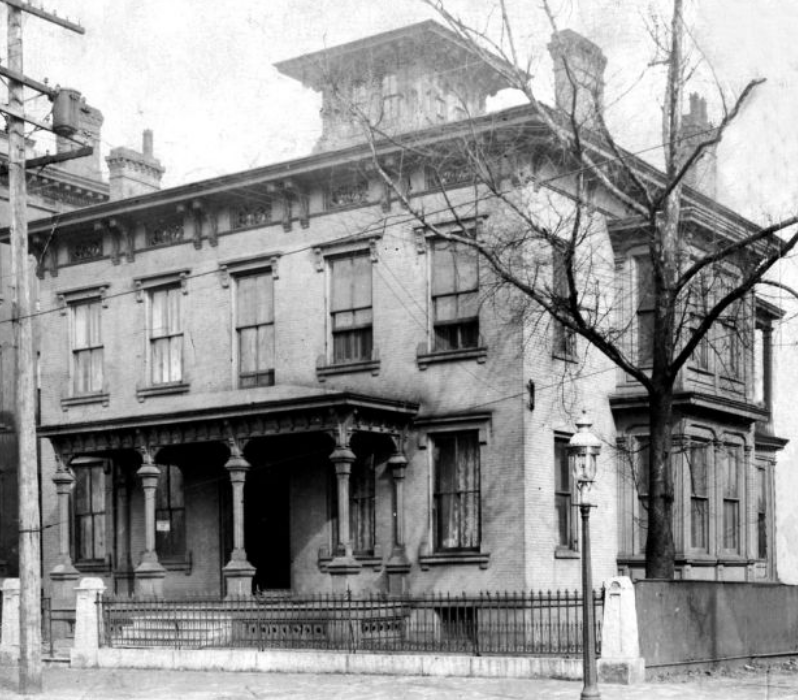

When the sewer was finally finished all the way to Vandeventer Avenue in 1890, it was considered the marvel of its time. It measured twenty feet wide, fifteen feet high, and more than three miles long. Wider than a single railroad track tunnel, the sewer pipe was described as large enough “to allow the passage of a train of cars or a four-horse omnibus.” The Shermans lived there for 11 years before moving back to New York City. When his wife, a devout Catholic, died in 1888, she was buried in Calvary Cemetery back in St. Louis. Three years later when the great man died, their children buried WTS (an Episcopalian) beside his wife.

The Shermans lived there for 11 years before moving back to New York City. When his wife, a devout Catholic, died in 1888, she was buried in Calvary Cemetery back in St. Louis. Three years later when the great man died, their children buried WTS (an Episcopalian) beside his wife. For four hours on February 21, 1891, a procession of 12,000 soldiers, veterans and notables marched past mourners on a winding, seven-mile path from downtown St. Louis to Calvary Cemetery.

For four hours on February 21, 1891, a procession of 12,000 soldiers, veterans and notables marched past mourners on a winding, seven-mile path from downtown St. Louis to Calvary Cemetery.

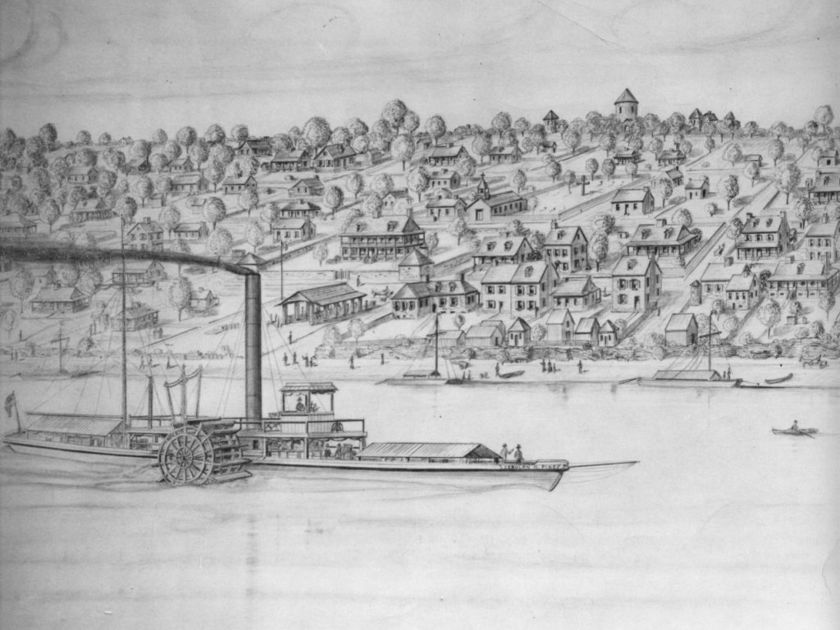

Two hundred years ago the first steamboat arrived in St. Louis on (or around) July 27, 1817. The S.S. Zebulon M. Pike was a small steamboat, and its underpowered engine needed help from old-fashioned poles in the hands of cordellers before it could tie up at the dock at the foot of Market Street. This was on the natural riverbank. By the 1830s, the landing was paved with limestone. The red granite levee that still exists was built in 1868-69.

Two hundred years ago the first steamboat arrived in St. Louis on (or around) July 27, 1817. The S.S. Zebulon M. Pike was a small steamboat, and its underpowered engine needed help from old-fashioned poles in the hands of cordellers before it could tie up at the dock at the foot of Market Street. This was on the natural riverbank. By the 1830s, the landing was paved with limestone. The red granite levee that still exists was built in 1868-69. Two months later a second steamboat arrived, the S.S. Constitution. Then the following spring, the S.S. Independence fought its way up the more challenging Missouri River as far as Franklin, about half-way across the soon-to-be state of Missouri. Next the S.S. Western Engineer, carrying the military/exploration party of Major Stephen Long, went up the Missouri as far as Council Bluffs.

Two months later a second steamboat arrived, the S.S. Constitution. Then the following spring, the S.S. Independence fought its way up the more challenging Missouri River as far as Franklin, about half-way across the soon-to-be state of Missouri. Next the S.S. Western Engineer, carrying the military/exploration party of Major Stephen Long, went up the Missouri as far as Council Bluffs. Thus St. Louis was transformed into a bustling inland port.

Thus St. Louis was transformed into a bustling inland port.