IL MIGLIOR FABBRO

by chuckofish

SILVER SPRING, Md. – Greetings from the Dual Personalities East Coast Poetry Bureau! Senior T. S. Eliot correspondent DN here to mark the centennial of an annus mirabilis in English letters, 1922, when three seminal works of literary modernism debuted: James Joyce’s Ulysses,Virginia Woolf’s Jacob’s Room, and T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land. October was the crux of this activity. Jacob’s Room was published on October 26, and The Waste Land appeared in the October 1922 issue—the first-ever issue!—of Eliot’s new literary quarterly, The Criterion. Talk about a side one, track one.

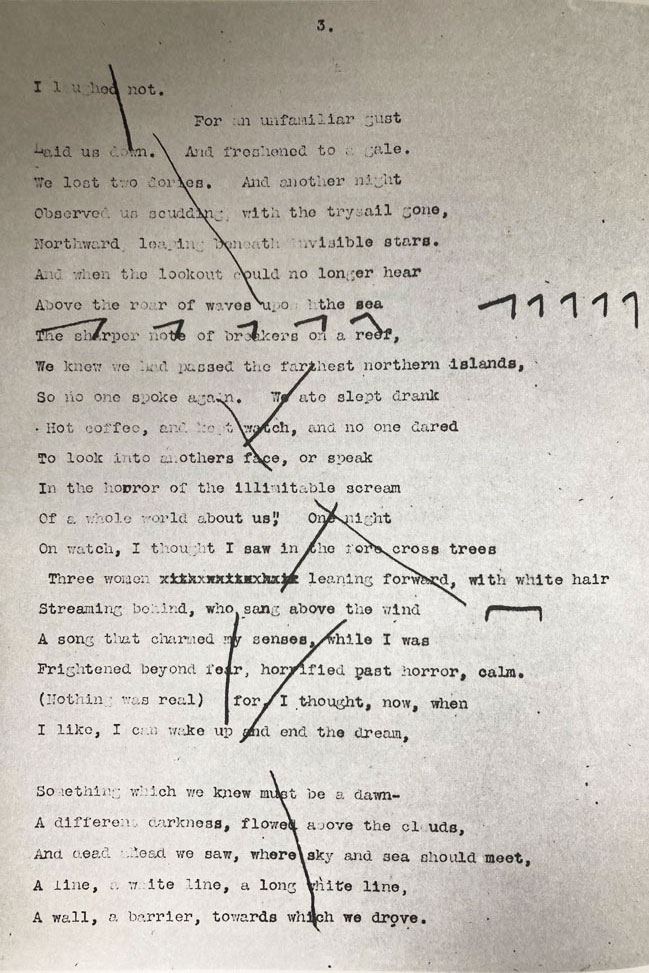

Both Woolf’s novel and Eliot’s poem break with formal conventions to treat the theme of loss after the Great War. Jacob’s Room is an elegy to a generation of young men struck down in their prime, while The Waste Land is (or is often interpreted to represent) an artifact of cultural loss in the century’s first decades. As you might expect from its title, the tone of The Waste Land is generally despairing. The poem reinforces this despair through its formal difficulty. Readers of The Waste Land encounter a cacophony of different voices and literary references juxtaposed without context or explanation. This obscurity is alienating: how on earth is this thing even readable? Such formal alienation is purposeful. Ezra Pound, to whom Eliot sent an early typescript draft, famously x-ed out entire sections of the poem to achieve this effect of obscurity.

Eliot dedicated the poem “FOR EZRA POUND / IL MIGLIOR FABBRO,” a phrase from Dante’s Purgatorio that translates to “the better craftsman.” A nice dedication, but “craftsman” is also kind of a dig. They were competitive guys! Still, Pound’s editorial eye was vital to the poem’s effects, in which compression of language reflects the alienation of industrialized, individualized, interwar modern life. And your modernist lit professor wants you not just to read but to reread it?! The poem is a hard sell.

In 1922, “hard sell” was literally true: the process of shopping the poem as a standalone book was exhausting, as Eliot continually sought to convince publishers that any readers would purchase it. Pound articulated a defense of the poem’s difficulty—its intentional obscurity—in a letter to Eliot: “Waste Land is one of the best things you [Eliot] have done … It is for the elect or the remnant or the select few or the superior guys, or any word you may choose, for the small number of readers that it is certain to have.”

For a work so self-consciously mandarin, The Waste Land continues to attract readers. There is something curiously engaging about it. The reader gets just enough—draws enough pleasure from the poem’s language, understands enough of its references—to continue reading on. Maybe you’re foolish enough to wish you were one of the “superior guys,” and you end up with a degree in modernist literature ¯\_(ツ)_/¯. This attraction was present in 1922 as well: all the cool kids wanted to be in the know, one of the small number of elect readers. A famous passage from Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited captures how the poem held cultural cache for the youth. In one scene, the trendiest member in a group of edgy aesthetes broadcasts the poem from a second story window.

After luncheon he stood on the balcony with a megaphone which had appeared surprisingly among the bric-a-brac of Sebastian’s room, and in languishing tones recited passages from The Waste Land to the sweatered and muffled throng that was on its way to the river.

“I, Tiresias, have foresuffered all.” he sobbed to them from the Venetian arches;

“Enacted on this same d-divan or b-bed, / I who have sat by Thebes below the wall / And walked among the l-l-lowest of the dead…”

I like this scene because it captures how Eliot’s poem, as a cultural phenomenon, was something that elicited big emotions. Languishing tones. Sobbing. On its face, this reaction might seem at odds with The Waste Land’s current reputation as a Difficult Poem™. However, in the 1920s, this complexity was central to its emotional force.

Today, your mileage may vary. If you’re of a certain mood and mindset, I think, the way that The Waste Land suspends meaning just beyond articulation can be stimulating. The poem dwells upon loss, yes, but it also holds out the possibility of generation or growth. The reason that cultural loss is so devastating is because this absence presents a conundrum for the future: How can we grow from here?

April is the cruelest month, breeding

Lilacs out of the dead land, mixing

Memory and desire, stirring

Dull roots with spring rain.

lines 1-4

These are the poem’s famous first lines, ones that present a barren land. But hark: on this ground, something grows. The land is infertile, but still, life is beginning. Stirred by rain, the dull roots appear to remember how live. They even desire to do so! But this desire is complex: the roots aren’t exactly choosing to live. Rather, they are being bred. The month is cruel. The roots seem more haunted by memory and compelled by desire than fully flourishing. They only persist—and barely at that.

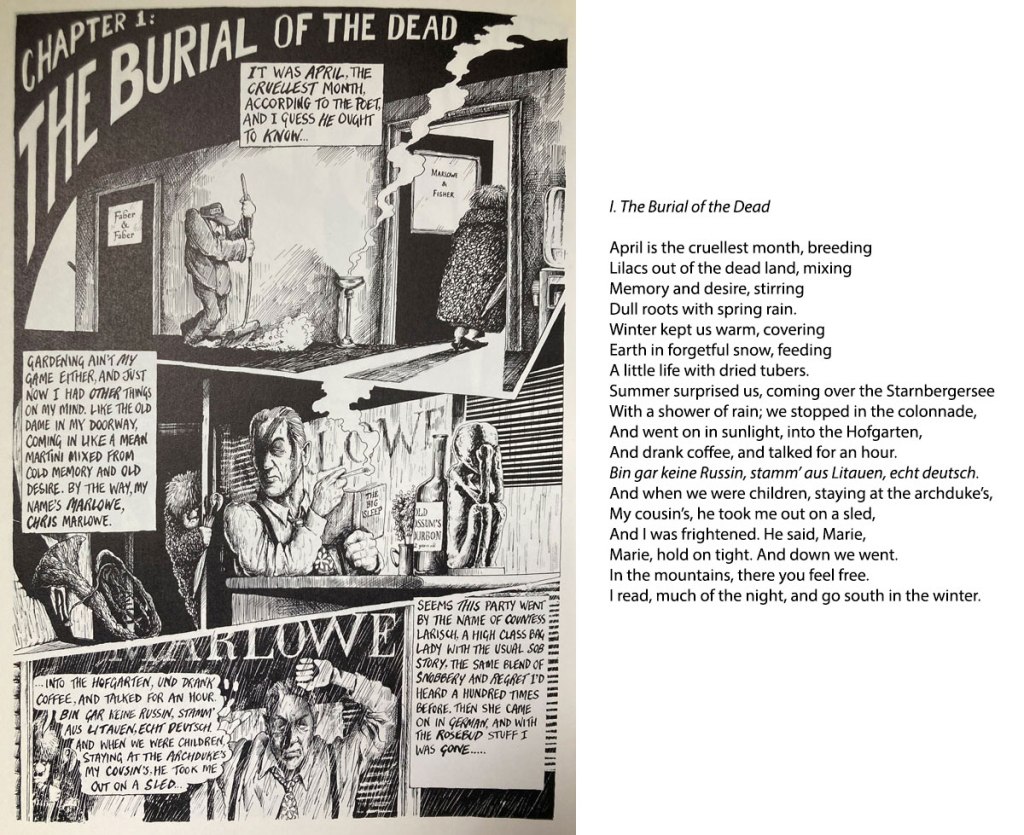

To the cartoonist Martin Rowson in 1990, this mixture felt familiar. Who else is haunted by memory, compelled by desire, and just barely eking out an existence? Who else is searching among opaque clues for a meaning or truth that just eludes them?

The transformation of The Waste Land into a Raymond Chandler mystery allegorizes the experience of reading the poem. Finding sense can be frustrating, yet it can also be stimulating.

Ultimately, Rowson’s graphic novel doesn’t hang together in its own right as a detective story. You need read it side-by-side with the poem…or, I suppose, have already memorized The Waste Land (but who would?). To me, that’s part of what I like about the comic. It’s not self-serious. Rather, it uses The Waste Land to generate something fun by translating the poem’s gloomy mood into noir. It is, as the kids say, a vibe. And vibes were very much part of The Waste Land’s appeal in the first place.

Unreal City,

Under the brown fog of a winter dawn,

A crowd flowed over London Bridge, so many,

I had not thought death had undone so many.

Sighs, short and infrequent, were exhaled,

And each man fixed his eyes before his feet.

Flowed up the hill and down King William Street,

To where Saint Mary Woolnoth kept the hours

With a dead sound on the final stroke of nine.

There I saw one I knew, and stopped him, crying: “Stetson!

“You who were with me in the ships at Mylae!

“That corpse you planted last year in your garden,

“Has it begun to sprout? Will it bloom this year?

“Or has the sudden frost disturbed its bed?

“Oh keep the Dog far hence, that’s friend to men,

“Or with his nails he’ll dig it up again!

“You! hypocrite lecteur!—mon semblable,—mon frère!”

lines 60-72

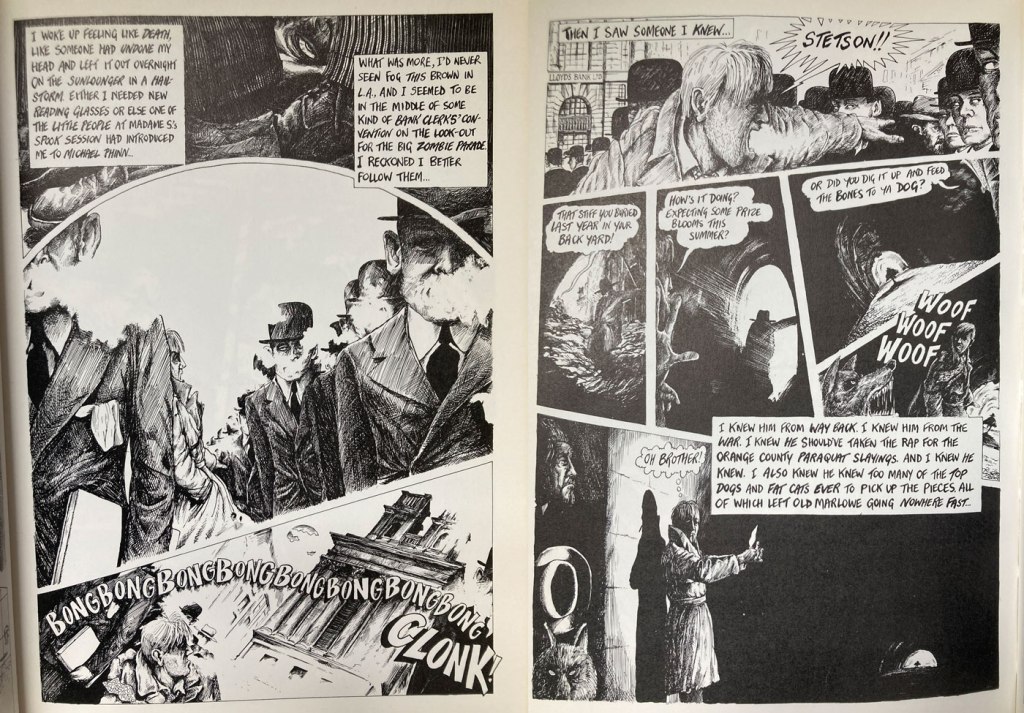

There’s lots of detail to enjoy here—the foggy crowd, Ezra Pound as Stetson, “mon frère” as “oh brother!”—but I especially love how the comic embraces The Waste Land’s approach to incorporating external cultural touchstones. In this case, on the middle panels of the second page, the imagery of the Vienna sewers from the famous chase scene in The Third Man.

Hey, I see what he did there! Maybe I really am one of the superior guys.

A wonderful contribution from the East Coast Poetry Bureau. Thank you for this read on Monday morning!

This made me feel a little bit smart again 🤓

Thank you so much for doing a guest shot on the blog! I can. identify with Ezra Pound and wanting to be one of the elect–I am a Presbyterian after all… Also the Raymond Chandler-esque noir rip-off was really something.

Thank you for the opportunity! I had a lot fun revisiting all the works.

In HS with Mr. Durgin, The Wasteland was beyond my ken. I could (to satirize his self-conscious modernity) stroke my imaginary chin whiskers, but that was, transparently, to feign understanding. Is it enough to have it so well laid out before me?

Ah well. Maybe I should give it another go. 🫤

I can’t imagine teaching TWL to high schoolers! Though I recall sitting through lectures in high school on Jacob’s Room and feeling totally overwhelmed. I’d be shocked if you told me I finished the novel then.

I’ve always liked The Waste Land, although I’m sure I don’t get it. Thanks for the stimulating post!

Oh no, I’m sure you do! It’s a vibe 🙂

Impressive, Nate! I always much preferred Prufrock tho. It’s much more quotable 😅

Totally. And I’ve heard it argued that the voice in Prufrock heralds the invention of modern poetry!