The fatal passion of a stubborn heart*

by chuckofish

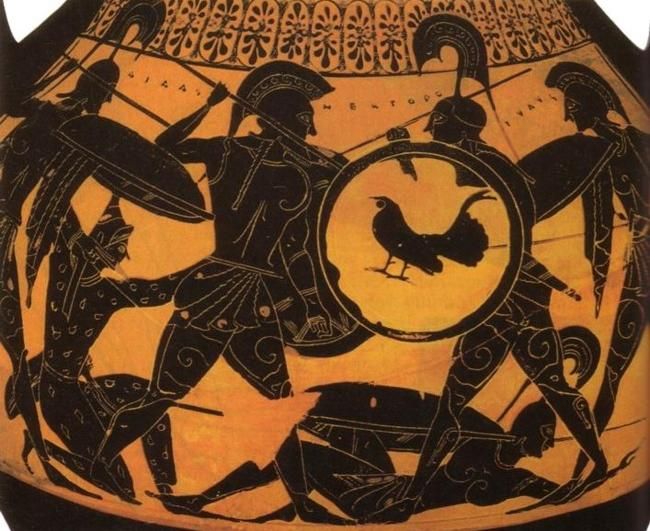

I just finished reading Sophocles’ Ajax and I loved it. You may remember that Ajax plays an important, if supporting, role in The Iliad. A fierce fighter and the cousin of Achilles, Ajax proves both thoroughly dependable and unwisely independent. He refuses the help of the gods because he wants to be his own man. In the play we discover the consequences of such freedom. Meanwhile, at Troy he guards the ships against the Trojan onslaught, tries to convince Achilles to return to the fight, duels Hector twice, and when Patroclus gets killed, fights to protect the corpse from vengeful Trojans.

Without doubt, his greatest feat involves recovering Achilles’ body and carrying it back to the Greek ships before the Trojans can plunder and mutilate it.

What does he get for all that faithful service? Nothing. Spurred on by Athena, who doesn’t like independent men, the Greeks award Achilles’ armor to Odysseus. Sophocles picks up the story at this point.

Certain that he has been cheated and dishonored, Ajax decides to kill as many of his former comrades as possible, starting with Agamemnon, Menelaus and Odysseus. Fortunately for them, Athena intervenes by driving him mad so that he mistakes herds of cattle and sheep for the Greek warriors. He slaughters, tortures and mutilates the animals, and when he comes to his senses, he is not only horribly ashamed but realizes that there is no escaping the gods and his dishonor. In an act of defiance (or shame), he kills himself by falling on his sword.

It’s a sad play that ponders the human condition with some lovely language:

Long rolling waves of time

bring all things to light

and plunge them down again

into utter darkness.

Like other Greek tragedies it boasts manipulative gods (Athena), angry men, weeping women and a stubborn, tragic hero who defies them all. It also has a lot to say to its audience. In particular I liked Teucer’s (Ajax’s half-brother) rousing speech against the autocratic Menelaus who forbids the burial of Ajax’s body:

Come, tell me once more from the beginning –

Do you really think it was you personally

who led Ajax here an Argive ally?

Did he not sail to Troy all on his own,

under his own command? In what respect

are you this man’s superior? On what ground

do you have any right to rule those men

whom he led here from home? You came to Troy

as king of Sparta. You do not govern us.

Under no circumstance did some right to rule

or to give him orders lie within your power,

just as he possessed no right to order you.

You sailed here a subordinate to others,

not as commander of the entire force

who could at any time tell Ajax what to do.

Go, be king of those you rule by right –

use those proud words of yours to punish them.

But I will set this body in a grave,

as justice says I should, even though you

or any other general forbids it.

It’s a speech that would have resonated with the Athenians in 440 BC (thought to be the date of the play’s performance). A fledgling democracy not yet a hundred years old, Athens was at the height of its power but in danger of succumbing to greed and hubris. Perhaps Sophocles thought his fellow citizens needed a reminder about what really matters: family, loyalty, and doing the right thing by upholding universal laws, particularly burial of the dead. Not that long after, he would bring up the same issue in Antigone. One wonders why Sophocles focused so on proper burial. I don’t suppose we’ll ever know.

I’ve got a busy weekend coming up and will have no time to ponder such matters. Tim and Abbie are coming for a visit – yay! Next week, I’ll tell you all about it. Have a grand weekend and always do the right thing!

*a line from the play. Translations by Ian Johnston. You can read the whole play online here. Ajax was a popular figure on Greek pottery. The photographs show several examples — all found via Google Image.