A porcelain life

by chuckofish

It was a ‘normal’ week. Nothing much happened, although I managed to get behind at work because I spent a lot of time researching the china I bought at an auction last weekend. I know what you’re thinking, and you’re right. The last thing I need is more china. What can I say? Consider it a rescue operation. My purchases came from a beautiful historic home in Sackett’s Harbor that had been in the same family for almost two hundred years. It’s a shame they decided to sell it all. Since I had no need or space for any of the furniture, I did not bid, but there were a few fun things — a Chinese gong and a couple of top hats that I thought would make great presents for my sons. Alas, other bidders with the same idea were willing to pay more than I. After a fun evening glued to my laptop, I ended up with this large, mixed lot of china, including several pieces that are beyond use or heavily repaired (the entire stack at the back left of the photo below), a few orphan cups,

a couple of modern pieces (duck teapot anyone?), some Canton Ware Chinese export porcelain, and several pieces of 19th century English transfer ware.

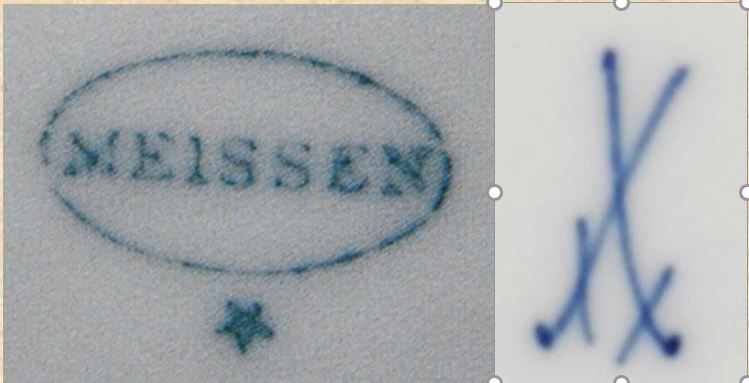

It’s quite a mish mosh, but as I said, I have had a lot of fun researching. For example, the cake stand is Copeland Delphi Grey (i.e. Spode) from about 1850-1860 — assuming it’s real. (You’ll notice there are two stands, but the one at the back on the right has been broken and repaired.) I’m doubtful because the collection includes other copies. The ‘Meissen’ blue onion plates in the top photo were actually made by another German porcelain maker calling itself the Meissen Oven and Porcelain Company. The company produced from 1882-1929. The mark gives it away; the one on the left in the picture below is the fake, while the crossed sabers mark on the right is authentic. Buyer beware! Sellers on Ebay and Etsy will simply claim ‘Meissen’ — after all, that’s what the mark says, right?

There are also some Royal Copenhagen style plates made by a German company called Koenigszelt that date to the early 20th century. At least Koenigzelt only borrowed the pattern and did not attempt to pass themselves off as Royal Copenhagen.

Of the four, lovely Coalport bone china plates from about 1880, only one is useable and even that has a slight chip on the lower rim.

I also identified a pretty Coalport cup and saucer set that I believe dates to the late 19th or early 20th century. As you can see from the photo, the pair saw hard use. There are tea stains I can’t remove and the gold edging has worn off — a rescue operation indeed!

I’m even less certain of the un-marked Canton Ware export porcelain and need to do more research. Based on my current state of knowledge, I’d say it was purchased here in America during the mid to late 19th century, although it’s also possible that someone bought it in China and that it’s modern. I’ll probably never know.

None of this mongrel collection is particularly valuable — indeed, I did not expect it to be — but I’m having a great time figuring out what each piece is and what I shall do with all of it. I have already boxed up the worst preserved of the lot, and I am rearranging some pieces so that I can display and/or use a few of them.

Judging from the ubiquitous cracks, chips and repairs, the family had epic arguments during which they threw dinnerware at each other. Either that or they had super clumsy servants. I prefer the passionate disagreement scenario. As Emily Dickinson wrote in a letter to a friend, “In such a porcelain life one likes to be sure that all is well lest one stumble upon one’s hopes in a pile of broken crockery.”* Although all is well and my own hopes cannot be found among my cracked and chipped purchases, I’m quite certain that I’ve met the vestigial hopes of the crockery-throwing owners. Now there’s a thought.

*Letter to Mr. and Mrs. Samuel Bowles, c. 1958