Gravel in her gut and spit in her eye*

by chuckofish

Recently, during one of our typically meandering conversations, the DH and I got to wondering whether The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance was based on a novel. We looked it up on IMDB, which attributed the original story (not the script) to Dorothy M. Johnson. It turns out that she also wrote the stories behind A Man Called Horse (1970) and The Hanging Tree (1959).

Now, everyone knows that The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance is a great film and one of director John Ford’s best, but let’s face it A Man Called Horse is mediocre to say the least (let’s be charitable). [You’ll be relieved to know that the two sequels were merely ‘based on the character in Johnson’s short story’.]

And even if it did star Gary Cooper, who has heard of The Hanging Tree?

None of this movie information told us much about Dorothy Johnson, so we dug around and discovered that she is quite a legend among Western writers. There’s even a short documentary about her life, from which I borrowed the title of this post.

In case you’re not up for watching a documentary, I’ll summarize briefly here. Born in Iowa in 1905, Dorothy and her family soon moved to Whitefish, Montana. After high school, she worked for the paper in Missoula, went to college, and did a stint as a writer in New York City before returning to Montana, where she spent the rest of her life. An early marriage ended in divorce, after which she took pride in her self-sufficiency and stayed single.

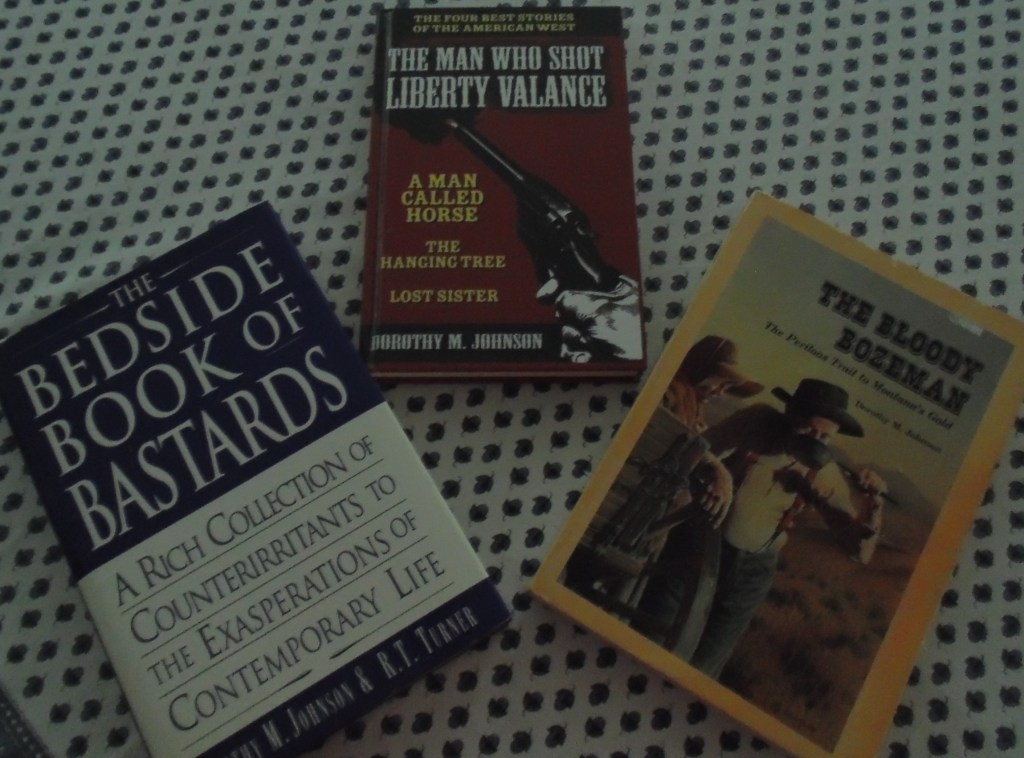

Intrigued, we ordered a couple of her books.

I haven’t started The Bloody Bozeman yet, and I’ve only read a couple of chapters from The Bedside Book of Bastards, which strikes one as a purely money-making gambit, but I did enjoy reading her collected tales. My brief assessment: The film version of the Man Who Shot Liberty Valance has much more to say than the short story, while (unsurprisingly) the story “A Man Called Horse” is better than the movie, as is the novella “The Hanging Tree”, though neither is great.

The best story in the collection is “Lost Sister” which has not been turned into a movie. It is loosely based on the case of Cynthia Ann Parker, who was stolen by the Comanches as a girl, assimilated into the tribe, and eventually married to a chief. Her eldest child was the famous Quanah Parker. As an adult of about 34 Cynthia Parker was returned to her white family, but could not adjust and died soon after. Johnson’s story is remarkably sympathetic to all the groups involved and does not take sides. Indeed, what makes Dorothy Johnson’s stories noteworthy is how authentic they seem. Her spare prose is suited to the subject matter. She seems to know how gold miners would behave, how difficult the return of a kidnapped girl (now a woman) would be for everyone involved, and what a feckless young man could learn from living among the Sioux.

Dorothy Johnson did not write great literature but she did capture something essential about life in the west. She was interested in people and did not let politics cloud her vision. Perhaps that’s why her stories have endured. By all accounts she was quite a character.

You can read her reminiscences about growing up in Montana here. This weekend, let’s raise a glass to Dorothy M. Johnson, Montana spitfire, honorary member of the Blackfoot tribe, and teller of tales.