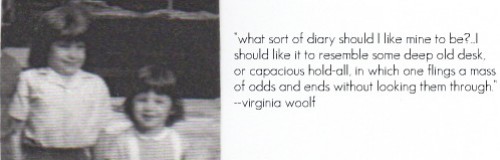

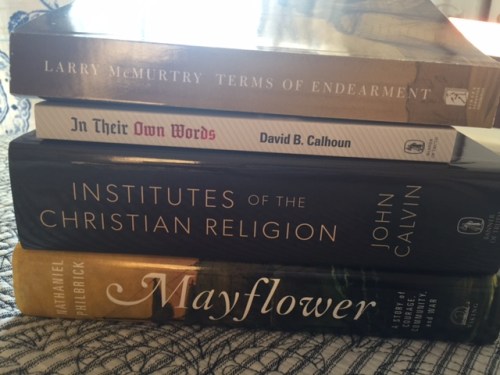

I still have most of the books I read in graduate school. And “most” is kind of a lot! I took my sweet time graduating. Occasionally, I pull something off the shelf that surprises me, particularly now, after moving, when everything has been shuffled and resorted. (Sometimes I pull down a book that, I quickly realize, does not surprise me. I promptly reshelve it. I should keep a list of books to cull.)

Lately, the most successful of these whimsical trips to our new-look bookshelf has yielded Evelyn Waugh’s Vile Bodies (1930)—a satirical novel recounting the escapades of the so-called Bright Young People of the late 1920s and early 30s—and Langston Hughes’s I Wonder as I Wander (1956)—the second volume of Hughes’s autobiography chronicling his travels between 1931 and 1938. On the surface, these two books and their authors seem to have little in common. Waugh was an upper-crust, white, Tory Oxonian. Hughes was a poor, black, Communist Kansan. However, both men share a wry distance toward the events of the 30s and their life in it. Waugh knows better than to take seriously the smart-set. Hughes circles the world and then some, never content that what he’s just seen is the final word. Both men, wise enough not to believe too firmly in their own opinions, look sideways at the 30s. Both men want to laugh at their times; they are in it but not of it.

Here are a couple of choice morsels. In Vile Bodies, Waugh combines economy of language with a withering anthropological eye.

They lunched at Chez Espinosa, the second most expensive restaurant in London; it was full of oilcloth and Lalique glass, and the sort of people who liked that sort of thing went there continually and said how awful it was.

No one has ever thought to diminish my existence in 40 words (as far as I know), but I shudder when I imagine Waugh giving me a quick up-down. The novel is not all sneer. It can lure you in with style, too. Feel how comfortable your eye gets when reading this description of being driven across the decaying grounds of a manor house. Then feel the sharpness of class distinction as your driver drops both you and his vowels.

They drove on for another mile. The track led to some stables, then behind rows of hothouses, among potting sheds and heaps of drenched leaves, past nondescript outbuildings that had once been laundry and bakery and a huge kennel where once someone had kept a bear, until suddenly it turned by a clump of holly and elms and laurel bushes into an open space that had once been laid with gravel. A lofty Palladian façade stretched before them and in front of it an equestrian statue pointed a baton imperiously down the main drive.

“‘Ere y’are,” said the driver.

I Wonder as I Wander is less overtly witty, but Hughes is a better observer and analyst. In the 1930s, Hughes bopped around the Caribbean before embarking on a book tour through the South. He washed up in San Francisco, after which he travelled back to New York to begin a stage production of his work just before sailing for the Soviet Union via Western Europe. Spending a year in the U.S.S.R. writing a film and another year traveling around Asia, Hughes finally finagled a ticket on the trans-Siberian railroad. Then he was thrown out of imperial Japan and spent another year in California, then to Mexico to bury his father, then back to New York, and then ultimately to Spain as a freelancer during the Spanish Civil War. That is to say, I won’t go too far into it, but Hughes has a lot of history to recount and a lot of nuanced opinions he wants to express. The best part about I Wonder and I Wander is Hughes’s endless drive to empathy. He often finds himself recalibrating his expectations or confirming his assumptions via skepticism.

I Wonder as I Wander is less overtly witty, but Hughes is a better observer and analyst. In the 1930s, Hughes bopped around the Caribbean before embarking on a book tour through the South. He washed up in San Francisco, after which he travelled back to New York to begin a stage production of his work just before sailing for the Soviet Union via Western Europe. Spending a year in the U.S.S.R. writing a film and another year traveling around Asia, Hughes finally finagled a ticket on the trans-Siberian railroad. Then he was thrown out of imperial Japan and spent another year in California, then to Mexico to bury his father, then back to New York, and then ultimately to Spain as a freelancer during the Spanish Civil War. That is to say, I won’t go too far into it, but Hughes has a lot of history to recount and a lot of nuanced opinions he wants to express. The best part about I Wonder and I Wander is Hughes’s endless drive to empathy. He often finds himself recalibrating his expectations or confirming his assumptions via skepticism.

Nichan and his girl would usually just lie there and talk quietly for a long time. But then, if I were still awake, beyond the partition I might hear in the middle of the night a terrific rolling and wrestling, scuffling, pushing, pulling, leaping and running about—which, when I first overheard such sounds, I thought they must be indicative of rape. Later I heard that it was just the way Uzbeks make love.

and

The restaurant’s presence confirmed something I had long suspected from observation, not only in the Soviet Union but around the world—even in places where there is almost nothing, the rich, the beautiful, the talented, or the very clever can always get something; in fact, the best of whatever there is.

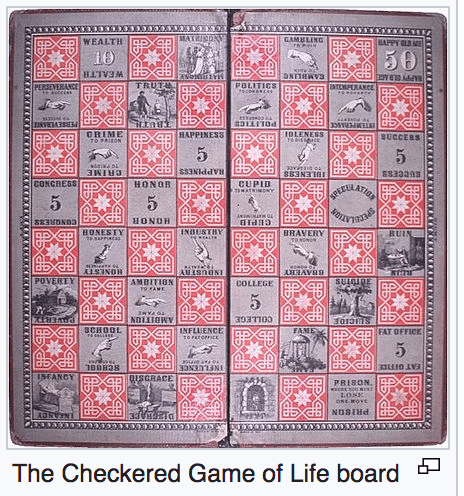

And sometimes I discover that what I thought was more recent—an original base for non-alcoholic cocktails—is in fact very old.

Breakfast at the Alianza consisted of a single roll and “Malta coffee”—burnt grain, pulverized and brewed into a muddy liquid. Sometimes there was milk, but no sugar.

At some point it hit me: what possesses me to stick with these books rather than reshelve them is a terrifying compulsion. I gravitate toward these texts as a symptom of that dread impulse of middle-aged men: I want to read … non-fiction. I might as well get cracking on the Davids—you know, McCullough, Halberstam, Sedaris.

Just please promise to set me straight should I think to start writing my own memoirs.

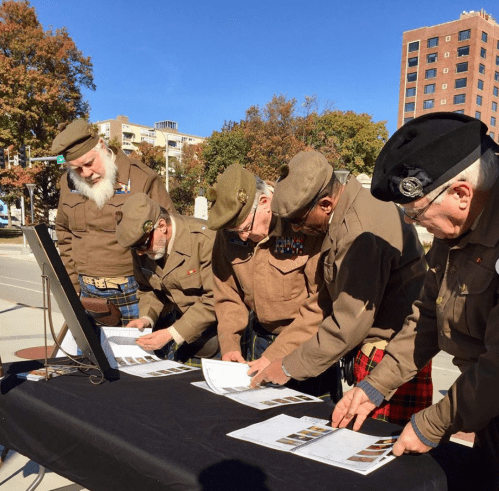

Well, here’s a great old hymn for Tuesday. We sing it in the Episcopal Church but with an organ accompaniment. However, I do like this rendition.

Well, here’s a great old hymn for Tuesday. We sing it in the Episcopal Church but with an organ accompaniment. However, I do like this rendition.

I Wonder as I Wander is less overtly witty, but Hughes is a better observer and analyst. In the 1930s, Hughes bopped around the Caribbean before embarking on a book tour through the South. He washed up in San Francisco, after which he travelled back to New York to begin a stage production of his work just before sailing for the Soviet Union via Western Europe. Spending a year in the U.S.S.R. writing a film and another year traveling around Asia, Hughes finally finagled a ticket on the trans-Siberian railroad. Then he was thrown out of imperial Japan and spent another year in California, then to Mexico to bury his father, then back to New York, and then ultimately to Spain as a freelancer during the Spanish Civil War. That is to say, I won’t go too far into it, but Hughes has a lot of history to recount and a lot of nuanced opinions he wants to express. The best part about I Wonder and I Wander is Hughes’s endless drive to empathy. He often finds himself recalibrating his expectations or confirming his assumptions via skepticism.

I Wonder as I Wander is less overtly witty, but Hughes is a better observer and analyst. In the 1930s, Hughes bopped around the Caribbean before embarking on a book tour through the South. He washed up in San Francisco, after which he travelled back to New York to begin a stage production of his work just before sailing for the Soviet Union via Western Europe. Spending a year in the U.S.S.R. writing a film and another year traveling around Asia, Hughes finally finagled a ticket on the trans-Siberian railroad. Then he was thrown out of imperial Japan and spent another year in California, then to Mexico to bury his father, then back to New York, and then ultimately to Spain as a freelancer during the Spanish Civil War. That is to say, I won’t go too far into it, but Hughes has a lot of history to recount and a lot of nuanced opinions he wants to express. The best part about I Wonder and I Wander is Hughes’s endless drive to empathy. He often finds himself recalibrating his expectations or confirming his assumptions via skepticism.

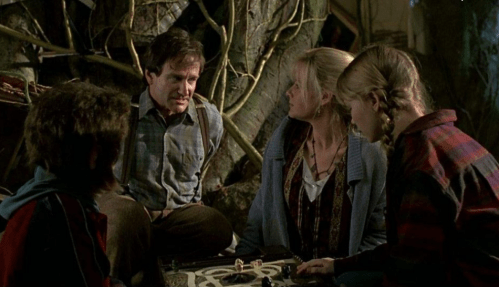

It’s definitely beginning to feel crisp and cold outside (hence the fire) and I’m looking forward to November and December. I’ve been thinking about Christmas cards and Thanksgiving side dishes and the best season for movie watching:

It’s definitely beginning to feel crisp and cold outside (hence the fire) and I’m looking forward to November and December. I’ve been thinking about Christmas cards and Thanksgiving side dishes and the best season for movie watching:

This is how my mind works after all…

This is how my mind works after all…