DN here with a surprise guest post!

The semester is in full-swing in College Park, and my former dissertation director recently sent me the syllabus for her graduate course. I have started reading along with the class in private. Last week’s text was T. S. Eliot’s Four Quartets, which sharp-eyed readers of this blog will recognize as part of the mental furniture of both DPs—particularly The Dry Salvages (1941), of course, seeing as it begins along the Mississippi River, but also Burnt Norton (1936) and Little Gidding (1942).

The church of St. John at Little Gidding

Burnt Norton, a Gloucestershire country house ruined by fire

Each of these poems takes its title from a place in Eliot’s past. Sometimes the setting arises out of the poet’s own experience—the gardens around Burnt Norton are where Eliot and his first wife, Vivienne, strolled during their courtship—and sometimes the location is a wishful projection of an ancestral past—Little Gidding was an Anglican settlement from the early 17th century that, as an experiment in religious life autonomous from church hierarchy, Eliot presents as a possible spiritual beginning (slash false-start) for all of England. Each poem is a trek into history animated by a question about the link between personal memory and public meaning, between individual experience and collective significance.

A people without history

Is not redeemed from time, for history is a pattern

Of timeless moments. So, while the light fails

On a winter’s afternoon, in a secluded chapel

History is now and England. (Little Gidding, lines 233-237)

How can history inform the present? In 1940 and 1941, when Eliot composed most of the Quartets, the present felt particularly formless. What future could arise from such rubble?

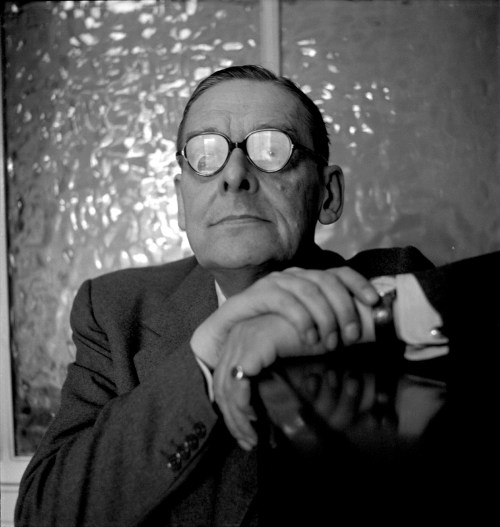

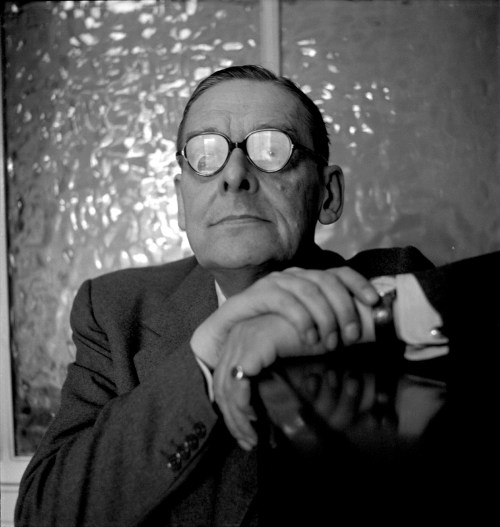

Eliot in 1956, standing before a textured glass partition in his Faber office

The general consensus is that Four Quartets tries to answer these questions via meditation. Knotting the reader into metaphysical quandaries, the poems arrive at enlightenment by challenging the very sense of its own sentences. This kind of poetry is hit-or-miss. It feels incredibly abstract until, after a few re-readings, parsing syntax again and again, some sort of sense emerges. But did this meaning come from the poem, or was it imposed by your own will to find meaning? In the face of the present’s formlessness, the poems make you self-aware of your own participation in supplying meaning. The Quartets’ abstraction fuels these sorts of questioning meditations, and they lead to idiosyncratic responses and interpretations for each reader.

The church of St. Michael in East Coker, where Eliot’s ashes reside today

The one poem from the Quartets not yet mentioned on this blog, East Coker (1940), the second in the series, is my personal favorite. I find the poem’s articulations of personal bewilderment very moving. The way that it uses rhythm to shuttle the reader between confusion and understanding is masterful. Below, for example, Eliot examines the life he lived between WWI and WWII, and he finds it wanting. The poet was fighting a losing battle against language. Paradoxically, nearly every phrase is quotable.

So here I am, in the middle way, having had twenty years—

Twenty years largely wasted, the years of l’entre deux guerres

Trying to use words, and every attempt

Is a wholly new start, and a different kind of failure

Because one has only learnt to get the better of words

For the thing one no longer has to say, or the way in which

One is no longer disposed to say it. And so each venture

Is a new beginning, a raid on the inarticulate

With shabby equipment always deteriorating

In the general mess of imprecision of feeling,

Undisciplined squads of emotion. And what there is to conquer

By strength and submission, has already been discovered

Once or twice, or several times, by men whom one cannot hope

To emulate—but there is no competition—

There is only the fight to recover what has been lost

And found and lost again and again: and now, under conditions

That seem unpropitious. But perhaps neither gain nor loss.

For us, there is only the trying. The rest is not our business.

I love the extended metaphor of one’s relationship to language as a struggle to marshal a disorderly army. I love the tone of the disillusioned commander putting on a brave face. For Eliot, the village of East Coker, from which his ancestor departed England for America in the 17th century, was both a literal and figurative starting point in the fight against disorder. But neither Thomas Stearns nor Andrew Eliot knew the outcomes of their respective endeavors. They simply set off (into language, into the Atlantic) with the hope of finding something meaningful.

Reading East Coker is like that too. The poem places me “in the middle way” such that understanding seems suspended just beyond reach. All too appropriate, given that I am no longer a student but that I am also not not reading for a class that I will not be attending. Eliot would appreciate the uncertainty.

The wee laddie approved.

The wee laddie approved.

It was a fun day and a fun weekend and on Sunday I even managed to go to a couple of estate sales with daughter #1. I rescued a needlepoint pillow!

It was a fun day and a fun weekend and on Sunday I even managed to go to a couple of estate sales with daughter #1. I rescued a needlepoint pillow!

The essay is about Elizabeth Stuart Phelps, who is one of my absolute favorite nineteenth-century women, and how she depicts domesticity in heaven.

The essay is about Elizabeth Stuart Phelps, who is one of my absolute favorite nineteenth-century women, and how she depicts domesticity in heaven.

There will be cake…

There will be cake… …and we will toast the birthday girl once, twice…thrice!

…and we will toast the birthday girl once, twice…thrice!

We had a very perfect weekend: sleeping in, drinking iced coffee, reading outside, walking on the trail, shopping at the farmer’s market. The weather was ideal, and our apartment feels more and more like home, especially because I have finally been able to hang a few things on the walls.

We had a very perfect weekend: sleeping in, drinking iced coffee, reading outside, walking on the trail, shopping at the farmer’s market. The weather was ideal, and our apartment feels more and more like home, especially because I have finally been able to hang a few things on the walls.

Here’s to a good week — and better luck with giveaway books!

Here’s to a good week — and better luck with giveaway books!