“They soon stopped being ten years old. But whatever age they were seemed to be exactly the right age for having fun.”*

by chuckofish

I have been slowly reading the essay collection Trick Mirror by Jia Tolentino, a staff writer at The New Yorker whose internet presence I also enjoy. (Well, I should say whose internet presence I did enjoy before I left Twitter.) These essays, which largely focus on millennial womanhood, are not exactly groundbreaking, but they are interesting and well written.

Tolentino first endeared herself to me when she Tweeted about attending a Betsy-Tacy convention in Minnesota. The Betsy-Tacy series is very dear to me — perhaps the first series of books I really loved — and I’ve even passed them on to girls I babysat. I also named my study abroad blog (wow–is that a specific genre or what?) after the penultimate book in the series: [SUSIE] AND THE GREAT WORLD. Maud Hart Lovelace seems relatively obscure, so any writer who understands that precise cultural reference is legit in my book.

In one of the essays from Trick Mirror, Tolentino writes about heroines of literature, from girls to young adults to women. She diagnoses that it is in children’s literature that female characters most flourish: there, they are adventurous and brave, their lives are thrilling and pleasurable. (The essay surmises that all literature about women tends towards darkness, though, and that marriage is the worst thing that can happen — to a plot and to a woman. I…don’t agree, but that isn’t my focus today!)

In one of the essays from Trick Mirror, Tolentino writes about heroines of literature, from girls to young adults to women. She diagnoses that it is in children’s literature that female characters most flourish: there, they are adventurous and brave, their lives are thrilling and pleasurable. (The essay surmises that all literature about women tends towards darkness, though, and that marriage is the worst thing that can happen — to a plot and to a woman. I…don’t agree, but that isn’t my focus today!)

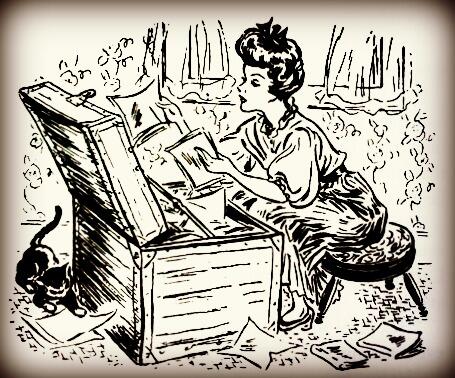

Girls, unlike women, can be unfettered, Tolentino suggests. In these books, the girl heroines are often writers themselves, and they forge spaces of their own in which to find their voice. This certainly applies to Betsy Ray, who Tolentino characterizes as “an unusual type” because she is “happy, popular, and easygoing” on top of being clever. It’s true! I was certainly drawn to Betsy because she was smart and she had friends and at least one boy liked her. Betsy was observant, she kept a journal, she wanted to be a writer, and she had a desk. (It was an old trunk. Very cool.)

I must have read the books in elementary school: probably third, fourth, and fifth grade. It occurs to me now that this must have been around the same time my mother starting writing her own novels, so perhaps my love for such literary girls were wrapped up in my own maternal example. Was it was some combination of wanting to be Betsy and wanting to be my mom that prompted me to write my own novel in a composition notebook? (Let’s not forget that it loosely plagiarized the Mitford series, so Jan Karon receives some credit here, too.)

Well, I certainly did not grow up thinking that marriage, or family, or homemaking, was the end of intelligence and independence, as some contemporary fiction would have you believe. (Tolentino gives far too much credit to Jeffrey Eugenides’s The Marriage Plot, if you ask me.) I find myself really wanting to re-read the Betsy-Tacy series now–perhaps we could all use the earnest optimism of our childhood heroines. After all, Tolentino concedes that children’s literature adheres to its own “wholesome logic” whereby “Laura Ingalls, Betsy Ray, and Anne Shirley all find husbands that respect them.” I guess that’s the trick!

*from Betsy and Tacy Go Over the Big Hill