The Second-Fastest Boy Runner in the World

by chuckofish

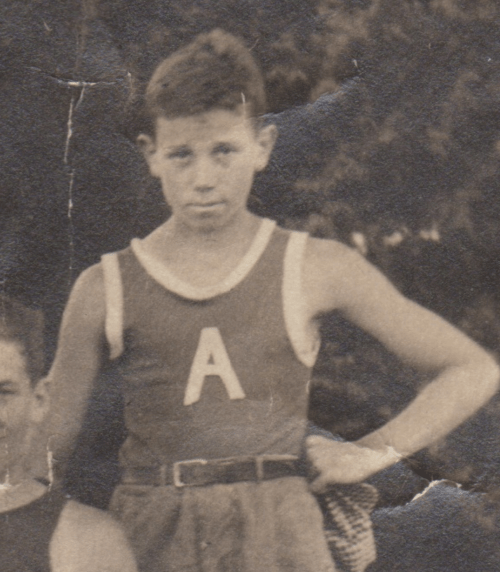

I was thinking about this ‘anecdote’ the other night and looked it up to read. It always reminded me so much of the boy when he was…a boy…and also, what I imagined my grandfather Bunker to be like.

It’s an Anecdote, sink me, but I’ll let it rip: At about nine, I had the very pleasant notion that I was the Fastest Boy Runner in the World. It’s the kind of queer, basically extracurricular conceit, I’m inclined to add, that dies hard, and even today, at a supersedentary forty, I can picture myself, in street clothes, whisking past a series of distinguished but hard-breathing Olympic milers and waving to them, amiably, without a trace of condescension. Anyway, one beautiful spring evening when we were still living over on Riverside Drive, Bessie sent me to the drugstore for a couple of quarts of ice cream. I came out of the building at that very same magical quarter hour described just a few paragraphs back. Equally fatal to the construction of this anecdote, I had sneakers on–sneakers surely being to anyone who happens to be the Fastest Boy Runner in the World almost exactly what red shoes were to Hans Christian Andersen’s little girl. Once I was clear of the building, I was Mercury himself, and broke into a “terrific” sprint up the long block to Broadway. I took the corner at Broadway on one wheel and kept going, doing the impossible: increasing speed. The drugstore that sold Louis Sherry ice cream, which was Bessie’s adamant choice, was three blocks north, at 113th. About halfway there, I tore past the stationery store where we usually bought our newspapers and magazines, but blindly, without noticing any acquaintances or relatives in the vicinity. Then, about a block farther on, I picked up the sound of pursuit at my rear, plainly conducted on foot. My first, perhaps typically New Yorkese thought was that the cops were after me–the charge, conceivably, Breaking Speed Records on a Non-School-Zone Street. I strained to get a little more speed out of my body, but it was no use. I felt a hand clutch out at me and grab hold of my sweater just where the winning-team numerals should have been, and, good and scared, I broke my speed with the awkwardness of a gooney bird coming to a stop. My pursuer was, of course, Seymour, and he was looking pretty damned scared himself. “What’s the matter? What happened?” he asked me frantically. He was still holding on to my sweater. I yanked myself loose from his hand and informed him, in the rather scatological idiom of the neighborhood, which I won’t record here verbatim, that nothing happened, nothing was the matter, that I was just running, for cryin’ out loud. His relief was prodigious. “Boy, did you scare me!” he said. “Wow, were you moving! I could hardly catch up with you!” We then went along, at a walk, to the drugstore together. Perhaps strangely, perhaps not strangely at all, the morale of the Second-Fastest Boy Runner in the World had not been perceptibly lowered. For one thing, I had been outrun by him. Besides, I was extremely busy noticing that he was panting a lot. It was oddly diverting to see him pant.

–J.D. Salinger, Seymour an Introduction

Classic Salinger. I love it. So. Much.

She saw Wuthering Heights when her family was spending the summer in New Hampshire with her “Aunt Laura”–not really her aunt, but an aged ancestor who owned “The Farm”. Stern old Aunt Laura took pity on Mary, when everyone went swimming, but left her at home because it was “her time of the month.” She drove her to town to see Wuthering Heights. It was a momentous occasion for my mother, because: 1. She loved the movie; and 2. Aunt Laura had done something really nice just for her. She never forgot and passed that tidbit on to me.

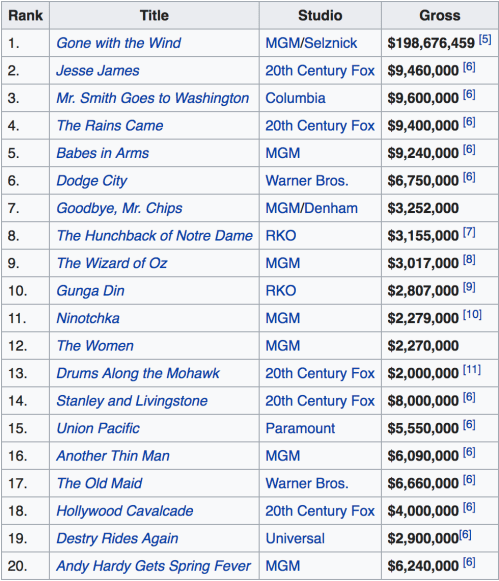

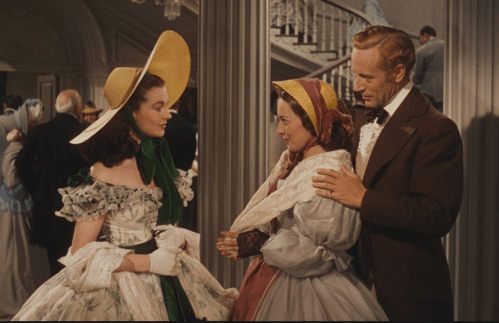

She saw Wuthering Heights when her family was spending the summer in New Hampshire with her “Aunt Laura”–not really her aunt, but an aged ancestor who owned “The Farm”. Stern old Aunt Laura took pity on Mary, when everyone went swimming, but left her at home because it was “her time of the month.” She drove her to town to see Wuthering Heights. It was a momentous occasion for my mother, because: 1. She loved the movie; and 2. Aunt Laura had done something really nice just for her. She never forgot and passed that tidbit on to me. My mother took me to see Gone With the Wind when it was re-released in 1969. I was in the seventh grade and it was a big deal because my mother took me and not my DP, who she deemed not quite old enough at 10 years old. I was the same age as my mother when she saw it in 1939. I was quite bowled over by the spectacle at the time, although there is not much I like about it now. (Okay, the music is good and I still love Leslie Howard.)

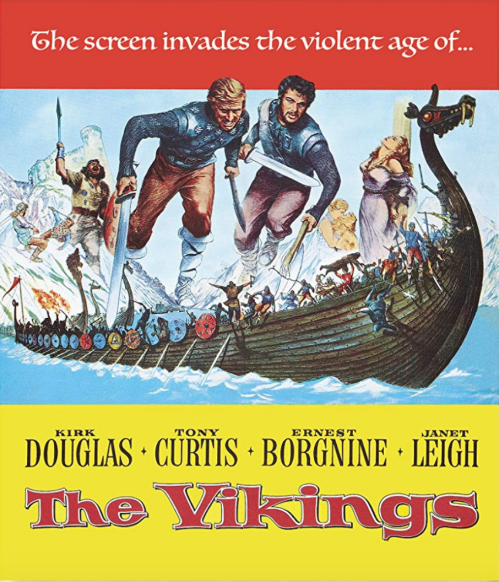

My mother took me to see Gone With the Wind when it was re-released in 1969. I was in the seventh grade and it was a big deal because my mother took me and not my DP, who she deemed not quite old enough at 10 years old. I was the same age as my mother when she saw it in 1939. I was quite bowled over by the spectacle at the time, although there is not much I like about it now. (Okay, the music is good and I still love Leslie Howard.) Movies nowadays, available on demand and at a moment’s notice, do not hold the same meaning as they did back in my mother’s day, and, indeed, in mine. For my mother, it was a once-a-week treat, and for me, it depended on television programming or what film series was being shown at the library or art museum. We went to see new movies once in awhile, but with nothing of the regularity of my parent’s generation.

Movies nowadays, available on demand and at a moment’s notice, do not hold the same meaning as they did back in my mother’s day, and, indeed, in mine. For my mother, it was a once-a-week treat, and for me, it depended on television programming or what film series was being shown at the library or art museum. We went to see new movies once in awhile, but with nothing of the regularity of my parent’s generation.